No more compelling figure has ever emerged from the pages of history than Joan of Arc, the brave peasant girl who heard the voices of angels and restored the dauphin to his rightful place on the throne of France. The mystery surrounding Joan’s story remains as mesmerizing today as it was when she first made her appearance some six centuries ago. How had the Maid, a lowly commoner, gained an audience at the royal court? How came she, an illiterate young woman from an insignificant, obscure, out-of-the-way village at the very edge of the kingdom, to know so much about the complex political situation in France, and, indeed, to see into the deepest recesses of her sovereign’s heart? What clandestine sign did Joan reveal to the dauphin that convinced him of her authenticity and inspired him to follow her advice? How did a seventeen year old girl with no experience in warfare defeat the fearsome English army and raise the siege of Orléans in a single week?

Now, to coincide with the 600th anniversary of the birth of Joan of Arc, for the first time all of these questions—and more—will be answered. Six hundred years is a long time to wait for the truth, but I promise you that the secret history of the Maid of Orléans is far more thrilling and fascinating than the myth that was so carefully and deliberately constructed around her those many years ago…

Bookshop.org Amazon Apple Audible Barnes & Noble Books-A-Million Kobo Amazon UKPraise for The Maid and the Queen

“Attention, ‘Game of Thrones’ fans: The most enjoyably sensational aspects of medieval politics—double-crosses, ambushes, bizarre personal obsessions, lunacy and naked self-interest—are in abundant evidence in Nancy Goldstone’s The Maid and the Queen… Because so much of this material is familiar, delivery becomes a crucial factor in any popular history of these events. Goldstone’s is vigorous, witty and no-nonsense in the tradition of the late, great popular historian Barbara Tuchman.”

—Laura Miller, Salon.com [read full review]

“Goldstone presents this dual biography of two fascinating medieval women with the descriptive energy of a novel.”

—USA Today

“Highly recommended for all readers who enjoy medieval history.”

—Historical Novels Society [read full review]

“The intrigues of the history and the miraculous unfolding of the story of Joan make the book seem as gripping as any novel… Until then, The Maid and the Queen stands as a fascinating new take on the legacy and legend of Joan of Arc, and a great introduction to the oft-overlooked Queen of Sicily.”

—Stephen Hubbard, Book Reporter [read full review]

“Goldstone has written a lively, fast-paced and fascinating account of Joan’s story, weaving together the labyrinthine intrigues of medieval politics, the real story behind a medieval fairy tale and the astonishing events that led a young peasant girl from the command of an army to a fiery death at the hands of the English. As in her previous books, Goldstone also sheds light on a little-known but admirable woman, Yolande of Aragon. The Maid and the Queen reminds us that, as Goldstone has remarked, ‘History makes a lot more sense when you put the women back in.'”

—Marianne Peters, BookPage

“The Maid and the Queen is a fascinating account of Joan of Arc, and the secret history of the powerful women behind France’s victory in the Hundred Years’ War. This is the story that you didn’t—and should—know. Recommended.”

—Devourer of Books

“Joan of Arc’s visionary leadership and legendary courage exemplify the medieval belief in the power of divine revelations and miraculous events that alter human history. At the height of the English siege of Orléans in 1428, a young woman mysteriously appeared in the court of Charles VII, urging him to march against the English troops and reclaim the crown of France. Yet, as Goldstone so forcefully reminds us in this tale of madness, mysticism, intrigue, and courage, we might never have heard of Joan of Arc if Yolande of Aragon, Charles’s mother-in-law and powerful queen of Sicily, hadn’t needed to convince him of his legitimate claim to the throne and bolster his courage in battle. Influenced by her reading of the popular Romance of Melusine—which featured a half-human, half-fairy heroine who helped a king achieve political success—Yolande chose Joan and her visions from God to help Charles triumph. With compelling storytelling, Goldstone colorfully weaves together the tales of these two women—one rich, one poor; one educated, one illiterate; one worldly, one simple—whose powerful personalities and deep allegiance to France helped shape the country’s future.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Once again, Goldstone, author of Four Queens (2007) and The Lady Queen (2009), looks to a supporting player to shed new light on an old subject. While Joan of Arc remains one of the most compelling heroines in the annals of history, the life of Yolande of Aragon, queen of Sicily, has been largely ignored by those outside the scholarly community. Goldstone corrects this oversight by presenting an intimate account of both of these women and the ways in which their paths and their missions converged. As mother-in-law of Charles VII, Yolande exerted a great deal of influence over the dauphin and consequently over the course of history when she championed an illiterate peasant girl claiming to have divine visions. A politically astute power broker, Yolande also employed her considerable administrative, logistical, and persuasive skills to save Orleans. Goldstone adds an enlightening new chapter to a legendary saga and rescues another unjustly neglected woman from the dust pile of conventional history.”

—Margaret Flanagan, Booklist

“A French noblewoman arranged Joan of Arc’s miraculous career. So argues popular historian Goldstone, who contends that Yolande of Aragon was deeply influenced by The Romance of Melusine, the story of a fairy aiding a young nobleman that she took as a blueprint for what needed to be done to goad France’s indecisive Charles VII into battle against English invaders. The author presents no hard evidence that Yolande even read the book, but Joan of Arc’s short life is nicely contextualized within the story of Yolande’s astute maneuvers among the shifting political currents of the Hundred Years War. It’s particularly valuable since there is no biography in English of this remarkable woman, thrown into the thick of European politics by her marriage to Louis II, a member of the French royal family who was also King of Sicily. Yolande administered her husband’s French possessions while he was consolidating his claim to Sicily, and she saw that her family’s security and prosperity depended on bolstering the resolve of Charles VII. Goldstone strongly suggests that Yolande was responsible for the prophecy that began to circulate around this time—’France, ruined by a woman, would be restored by a virgin from the marches of Lorraine’—though she’s too conscientious a historian to state outright that the prophecy prompted Joan’s hearing divine voices. It’s possible that Yolande smoothed Joan’s path to Charles and encouraged his acceptance of her as literally heaven-sent, though again there’s no hard proof. Nonetheless, Goldstone’s vivid retelling of Joan’s astounding victories and her capture and martyrdom by the English is as gripping as ever, and she brings Yolande back into the narrative following Joan’s death in 1431 to spur Charles to a truce with the powerful duke of Burgundy, which ultimately led to the French victory. Readers don’t have to buy the shaky premise to enjoy this knowledgeable and accessible account of a turning point in French history.”

—Kirkus Reviews, February 1, 2012

Since there seems to be some confusion about the role The Romance of Melusine played in the Joan of Arc narrative, let’s talk about why the book is so important:

First of all, what is this book The Romance of Melusine?

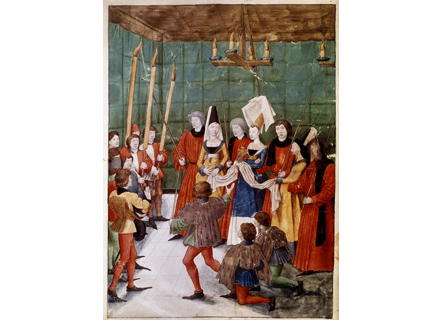

The Romance of Melusine was a novel written by Jean of Arras in 1392 at the express wish of Jean, duke of Berry, and his sister Marie, the duchess of Bar. The duke of Berry was an uncle of the then king of France, Charles VI; the duchess of Bar was the king’s aunt. The novel tells the story of Raymondin, a young nobleman who accidently murders his cousin and is helped out of his predicament by Melusine, a beautiful woman, half-fairy, half-human. Raymondin marries Melusine and, following her political and military advice, becomes a great lord before he ultimately betrays her.

The Romance of Melusine was a hugely popular and influential work, especially in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. It was translated into many languages and with the arrival of the printing press, went through twenty editions in French in the fifteenth century alone.

Well, if it is so important why have I never heard of it?

Probably because it has never been translated into accessible English. The only affordable English translation currently available is an archaic old English translation of a later 16th century Trinity College, Cambridge manuscript translated by the Reverend Walter W. Skeat, M.A., called The Romans of Partenay or of Lusignen otherwise known as the Tale of Melusine. Even from the title I think you can tell that this translation is very difficult to understand so I am not at all surprised that the book is unknown here. Luckily, there will be a new, highly accessible, absolutely charming translation available from the Pennsylvania State University Press in fall, 2012 written by two of the leading scholars in the field, Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox, both professors of French and Italian at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Professors Maddox and Sturm-Maddox have been studying the text of Melusine for decades and were responsible for organizing an international medieval colloquium, “Melusine at 600,” at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst in November, 1993. They are also the editors of the authoritative work on the subject, Melusine of Lusignan: Founding Fiction in Late Medieval France (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996).

How on earth could a novel—and a fairy tale at that—be used to further political designs? That doesn’t make any sense.

Actually, it makes quite a bit of sense if you happen to be talking about the Middle Ages. Often people did believe in fairies or other spirits, or saw evidence of their existence in the world around them. They sometimes blurred the line between reality and the supernatural. I make this point very strongly at the beginning of The Maid and the Queen. Yolande of Aragon in particular grew up at a court that believed that works of poetry or literature could influence the course of human affairs. This romantic conviction occasionally also strayed into domains ordinarily associated with religion. For example, Yolande once built a chapel on a spot where a rabbit leaped into her lap because she took it as a sign from God.

But The Romance of Melusine was even more likely to be referenced by fourteenth and fifteenth century nobility in times of upheaval because the book was very specifically written to address a political problem. The duke of Berry had appropriated a castle that didn’t belong to him and this had created unrest among his subjects. Jean of Arras was the duke’s secretary and he deliberately fashioned the story of Melusine to address this issue. Again, I took pains to make this very clear in The Maid and the Queen. Everyone who read the book at the time understood that it was as much a political tract as it was a fairy tale. In fact, it was almost an instruction manual—a sort of political how-to book. Nor was the duke of Berry the only person to profit in this way from the novel; according to Professors Maddox and Sturm-Maddox, “[Melusine‘s] popularity during the later Middle Ages is attested by the fact that it served twice to further political designs, once in Jean [of Arras]’s prose text, then in… a version composed under English patronage some ten years later by a certain Coudrette.” (It is Coudrette’s manuscript, a copy of which ended up at Trinity College, Cambridge that the Reverend Walter W. Skeat translated.)

Okay, so The Romance of Melusine was an important book in its day. But how do you know Yolande of Aragon even read this work? Did she write a book report on it or something for school?

Alas, no, I only wish she had. But there is a great deal of evidence linking Yolande of Aragon with this novel. Scholars who research a period as long ago as the Middle Ages—remember that we are talking about events that occurred over six hundred years ago—understand that many, many documents have been lost due to age and war and so they are often forced to rely on a body of evidence and to deal in probabilities. Was something likely, highly likely, unlikely, or highly unlikely? In the case of Yolande of Aragon, we know that her maternal grandmother, the duchess of Bar, requested that the book be written because Jean of Arras said so explicitly in his introduction to The Romance of Melusine, which he also dedicated to her. We know that Jean of Arras actually wrote Yolande’s parents, the king and queen of Aragon, into the book as important characters who played a large role in the story. We know that in real life the king and queen of Aragon were great supporters of the arts and the queen of Aragon, in particular, had been known to write to her mother, the duchess of Bar, to please send her more books. It is therefore highly unlikely that the court of Aragon, where Yolande of Aragon grew up, was unfamiliar with The Romance of Melusine. More than this, Yolande of Aragon was herself known to be a great reader and to have amassed a substantial library. She is on record as haggling with a bookseller over the price of a particular manuscript. When the duke of Orléans was captured at Agincourt, she brought his library to her castle at Saumur for safekeeping. Finally, Yolande’s second son, René of Anjou, who later became duke of Bar and Lorraine (the region of France where Domrémy, the village where Joan of Arc was born, was situated) actually gave a copy of The Romance of Melusine to Charles VII, the man who Joan called the dauphin and who she led to be crowned king at Reims, in 1444. It is highly unlikely that René knew of the existence of a book that was very important to his mother’s family, and that was published during his mother’s childhood, seventeen years before he was born, of which his mother remained oblivious.

In the language of scholarship, all of these facts taken together meant that it was almost impossible that Yolande was unaware of, or had never read, The Romance of Melusine.

So okay, Yolande of Aragon read The Romance of Melusine. But Joan’s life does not replicate Melusine’s story exactly. You can’t pick and choose like that from a narrative and expect people to believe that this was the inspiration for Yolande’s soliciting a mystic like Joan of Arc.

Well, actually, you can, especially when the narrative in question functioned as much as a political and military instructional manual as it did a work of literature. The Romance of Melusine offered very explicit advice to princes and other noblemen who found themselves in difficulties. Among its many lessons were helpful discourses on (1) how to get back your inheritance if you felt you had been unfairly cheated out of it (a situation certainly applicable to the dauphin, who had been deprived of the throne of France by Henry V); (2) how to turn a murder into an accident and thereby gain political capital from it (the dauphin murdered the duke of Burgundy on a bridge in 1419 but never took responsibility for the act, always claiming it was an accident); (3) how to prepare your army for war (make your knights wear their armor on the way to a battle no matter how much they complained as that way they would be used to the weight when it came time to fight); (4) strategies for winning a war based on historical precedent; (5) how to isolate your enemies and win allies to your cause (something Yolande was always trying to get the dauphin to do); in short, how to succeed politically and militarily. The advice comes from Melusine, who introduces herself to Raymondin as follows: “In God’s name, Raymondin, I am, after God, the one who can help and advance you the most in this mortal world in whatever adversity befalls you… I am sent by order of God… May you also know with certainty that without me or my advice you cannot accomplish your goals… for I will make you the most noble, most sovereign and greatest member ever of your lineage, and the most powerful mortal on earth.”

The parallels are so striking that it seems almost inconceivable that, once the dauphin had murdered the duke of Burgundy and was subsequently disinherited, Yolande would not have made the connection to this book.

Well, if this is so obvious, how come no academic or more credentialed person has come up with this? What makes you think that you know more than someone who teaches medieval history at a university or written a scholarly book on Joan of Arc?

Nearly every book on Joan of Arc, academic or otherwise, begins with Joan’s birth and seeks to understand events from her point of view. Unfortunately, it is impossible to grasp the overall situation from this perspective, as Joan herself was unaware of Yolande’s influence. Joan believed that everything that happened to her was a result of her own actions or the intervention of her angels.

A number of scholars have hypothesized that Yolande had something to do with Joan’s story but they don’t know how, or why. This is because there has never been a biography of Yolande of Aragon in English before mine and it is absolutely necessary to trace her political development through the serpentine avenues of the Armagnac-Burgundian civil war, which began with the assassination of the duke of Orléans in 1407, five years before Joan was even born. And the handful of biographies of Yolande in French also overlook her role in the Joan of Arc narrative because they don’t go back to her grandmother’s court and so miss the Melusine connection.

Similarly, scholars who specialize in The Romance of Melusine are generally far more interested in its artistic merits than in its political influence. They tend to know a great deal about medieval literature and very little about the politics of the second half of the Hundred Years War, particularly from the French side, which admittedly can be very confusing. Even when they notice the similarity between Joan of Arc and Melusine, as Nadia Margolis, a medieval literature specialist, did in a scholarly article entitled “Myths in Progress: A Literary-Typological Comparison of Melusine and Joan of Arc,” she failed to see Yolande of Aragon as the real world link between the two because it is clear she had never heard of her.

Read about Joan of Arc in the Los Angeles Times

Celebrating the real Joan of Arc: She earned our respect with her courage, not by virtue of a tale about her birth date.

A Conversation with Nancy Goldstone

Ordinarily, you write about unknown people in history. With this book, did you set out to write about Joan of Arc?

Alas, no. Joan of Arc is famous. I don’t write about famous people, I write about important, powerful women in history who no one has ever heard of. There were dozens of them in the Middle Ages. The woman I initially set out to investigate was Yolande of Aragon, fifteenth century queen of Sicily, duchess of Maine and Anjou, and countess of Provence. Bet you never heard of her.

Who was Yolande of Aragon and how is she remembered in history?

Yolande of Aragon was the predominant politician in France during the second half of the Hundred Years War. She was the de facto leader of the Armagnac party from 1417 until her death in 1442. As duchess of Maine and Anjou she owned outright or was regent for substantial property in France, including the all-important fortress of Angers. She was also, by coincidence, the dauphin’s mother-in-law. She chaired his council and occasionally, when the need arose, took over his court. In her own day she was both revered and feared. Today, she is almost completely unknown.

You write convincingly of Yolande’s influence over Joan’s rise to prominence. Why do you think this evidence has remained uncovered for 600 years?

There are many reasons that Yolande’s role in the story of Joan of Arc has been overlooked for so long. For example, most biographers approach the material from Joan’s perspective. They begin their study with her birth, and follow her personal development. By doing so they miss Yolande’s influence because Joan herself was unaware of it. Joan believed that everything that happened was the result of her own actions or the intervention of her angels.

Also, there is the problem that the study of medieval history was for centuries dominated by men who were simply not that interested in delving into the lives of the women of the period. It’s changing now but there is still the prejudice that women’s roles were secondary.

A further impediment is that so much of academia is specialized—military historians concentrate on war; scholars who focus on politics don’t take into account the influence of culture; people who study the literature of a certain era are probably unfamiliar with the convoluted statecraft of a slightly later time period. I bridge the gap between all of these different groups.

How did you come across this story given that it’s buried in the annals of history?

I was almost ludicrously positioned to stumble across this story. I love poking around in the lives of aristocratic women and investigate, not only my subject’s childhood and background, but her mother’s (and frequently her grandmother’s) life as well. I am well aware from my previous books that a queen can wield just as much political power as a king or prince—and sometimes more. I have also written extensively with my husband about old and rare books and have traced the trajectory and influence of forgotten volumes on the course of history. I know to look at provenance, to follow a particular title’s popularity, to see who owned the book over time as a means of measuring its impact. All of these seemingly disparate elements were necessary to uncovering the secret history of Joan of Arc.

Can you explain a bit more about how your previous work led you to write about Joan of Arc and the Hundred Years War?

A few years ago, I wrote a book called Four Queens, about a family of four thirteenth century sisters, the daughters of the count of Provence, who all became queens—queen of France, queen of England, queen of Germany and queen of Sicily. Theirs was an extremely important family and it was almost impossible to understand the dynamic of 13th century Europe without them. While I was researching that book, I stumbled across the story of one of their descendants, Joanna I, fourteenth century queen of Naples, Jerusalem and Sicily, and countess of Provence. Joanna was even more amazing and influential than her ancestors—she was the only woman of her day to inherit and rule a major European kingdom in her own right. She became the subject of my next book, The Lady Queen. After I finished writing about Joanna, having looked into both the 13th and 14th centuries, I couldn’t help but wonder—and I’m sure you can see a pattern here—what happened to my queens of Sicily and countesses of Provence in the fifteenth century? Were any of them important? And that is how I came to Yolande of Aragon, the most powerful woman of her time—and certainly one of the most capable women of any time! And Yolande led me directly to Joan.

With the addition of Yolande, what’s new in The Maid and the Queen that changes our commonly held narrative?

For centuries, Joan of Arc’s story has been an enigma. An illiterate peasant girl hears the voices of angels who instruct her to raise the siege of Orléans, expel the English from France, and lead her king to be crowned at Reims. Believing herself to be a messenger from God and the subject of a divine prophecy, she approaches a captain in the French army who agrees to send her to the royal court. Once there, she reveals a secret sign to the dauphin that convinces him of her authenticity. She subsequently leads the French army to the relief of Orléans, raises the siege in a single week, and makes good her vow to see her king crowned at Reims. The Maid and the Queen unravels this mystery by providing the method and motive for Joan’s introduction to the royal court and the manner in which she came to know so much about the dauphin and the war. It reveals the secret sign she presented to him. It explains how she came to lift the siege of Orléans. It is a completely new interpretation of events, the uncovering of a narrative that was deliberately hidden for political purposes.

Why does placing Joan in this new context matter so much to understanding her story?

Placing Joan’s life in the context of what was happening around her both politically and militarily is absolutely central to understanding her story. For far too long the events of the civil war between the Armagnacs and Burgundians have been sloughed over, not to mention the day-to-day operations of the English occupation. To give just one example, everyone knows that Joan’s angels told her to relieve the siege of Orléans. But the English did not begin besieging Orléans until October 1428, so Joan’s voices would not have told her to come to Orléans aid until the fall of that year. Yet she made her first attempt to see Robert de Baudricourt nearly six months earlier, in May 1428. Those who placed Joan’s action in context would understand that she was reacting to the news of a war council the English were holding in Paris that month. So information from as far away as Paris traveled quickly to Domrémy. An historian who put Joan’s story into context would wonder not simply what Joan herself was thinking but what others in power were thinking. Who might have had a motive for introducing a mystic into this volatile situation? (I remind you that as late as the 1980s, Nancy Reagan smuggled an astrologer into the White House to read Ronald Reagan’s horoscope.) Where might the inspiration for such an unusual intervention have come from?

What was most difficult about writing about an iconic figure like Joan of Arc?

Stripping away preconceptions and staying in the moment—not letting what I knew about her intrude on the depiction of events in her life. For example, when Joan arrived at the royal court at Chinon and requested an audience with the dauphin, I knew that she had come from Domrémy in the duchy of Bar (where Yolande’s second son was the duke) but the dauphin and the vast majority of his advisers and the rest of the court did not. To them, she just materialized out of some far away part of the kingdom. Similarly, when Joan was captured in battle, I knew that she would be sold to the English, subjected to a trial by the Inquisition, and then burned at the stake. But the king and his court had no reason to believe or even suspect that this would happen as it was entirely outside the rules of chivalry that governed the treatment of captured soldiers.

Historical novelists like Philippa Gregory regularly employ the fairy Melusine in their books. How does this mythical character present itself in Joan’s story? How does the historical account different from the fictional?

Historical novelists generally use Melusine as a romantic literary device, focusing on the male betrayal of a woman in love. Ironically, the story was originally written as a political allegory—a means of putting a patriotic spin on an otherwise questionable act of partisan self-interest. Sophisticated readers familiar with the story in the 14th and 15th centuries understood this and the evidence strongly suggests that the fairy tale was deliberately employed to help pave the way for Joan of Arc. Of course, someone who writes fiction is under no obligation to get the facts straight but personally I find the narrative behind Melusine to be far more amusing and relevant than the sentimental version favored by romance novelists.

This is now your fourth book set in the Middle Ages. What attracts you to this time period?

Who wouldn’t want to write about the Middle Ages? These are the best stories in the world! Kings, queens, knights, ladies, double-dealing, back-stabbing, triple-dealing, spies, treason, treachery, love affairs, scandals, invasions! Modern action films are tame next to this stuff. And don’t think none of this is relevant to today—I saw Afghanistan in every twist and turn of the Hundred Years War while I was writing The Maid and the Queen.

How would you like this new information to be received?

No one admires Joan of Arc more than I do. I have lived with her story, breathed her heartbreakingly short, electric, irresistible existence for years now and I believe her to be one of the most inspiring and courageous individuals in all of history. That’s why I feel it is so important to get her story right, that the truth about her not be obscured. Joan is like an amazing dress, breathtaking in its simplicity, which has been bestrewn with gaudy ribbons and cheap lace and rhinestones. It is only by stripping away the gewgaws that the power and purpose of her soul is revealed. To penetrate the legend that has grown up around her takes nothing away from Joan’s story—rather, it is the myth itself that does not do her justice.